Astronomy through the Ages - C21st and Afterword

Back to the Index of I2AO (Introduction to Astronomy Online)

ASTRONOMY THROUGH THE AGES: The Twenty-First Century and Afterword by Ian Kemp and Lesa Moore

- 2007 – Terry Lovejoy

- 2007 – Vandi Verma

- 2020 – Afterword

-----------------------

44: 2007 – Terry Lovejoy

Author: Ian Kemp

Amateur astronomer at wor... oh! Honestly, if you live just 18 km from the centre of Brisbane, beset by light pollution, with a Celestron SCT in your backyard, there ain’t going to be much serious science you can do, right? Well Terry Lovejoy (and I) would beg to differ. Terry realised that the big advantage that an amateur has over a professional is the ability to image large parts of the sky repeatedly, using large amounts of telescope time, which is rather different from the way professionals operate - they usually look at specific targets using the absolute minimum of highly contested telescope time.

Terry decided to start collecting images of large swathes of the sky, and wrote some software called “MOD” (Moving Object Detection) to compare images of the same region and highlight things that differ from time to time. A nice idea, but don’t think this means you can just sit back and get a list of new asteroids, supernovae and comets delivered by email as you eat your Cornflakes. Terry opted to collect his images at high sensitivity, meaning that the MOD system produces lots of ‘false positives’ - noisy bits in the images masquerading as new objects. In a crowded star field like the Milky Way, 90% of detections can be false, so his day begins by checking a long list of detections, manually, one by one. The actual detections are usually catalogued planets, asteroids or satellites, but every now and then he hits paydirt - something new! Terry has discovered six comets, including most famously C/2011 W3 (Lovejoy), the first Kreutz-Sun-grazer (fragment of an earlier comet) discovered from Earth-based observation since the 1970s.

Six comets in 10 years is an impressive record and gives you some idea of the amount of commitment required to get results in this field. After making a discovery, comes the nail-biting period when the finder has to contact another astronomer (e.g., someone in South Africa or South America) who can duplicate the image. Only then can it be reported to the recognised international hotline … and the longer this process takes, the more chance of being gazumped by someone else! The earlier a comet is discovered, the sooner the professional astronomers can interrupt their normal programs and turn their multi-million-dollar big guns on the target - hence getting more and better data. In this way, amateur astronomers like Terry make a heavy contribution to our subject.

Terry was born in 1966 and is still going strong. If you’re reading this Terry, thanks and please correct any errors!

Figure 44.1 below - Terry Lovejoy

Image Credit: Amy & Sarah Lovejoy

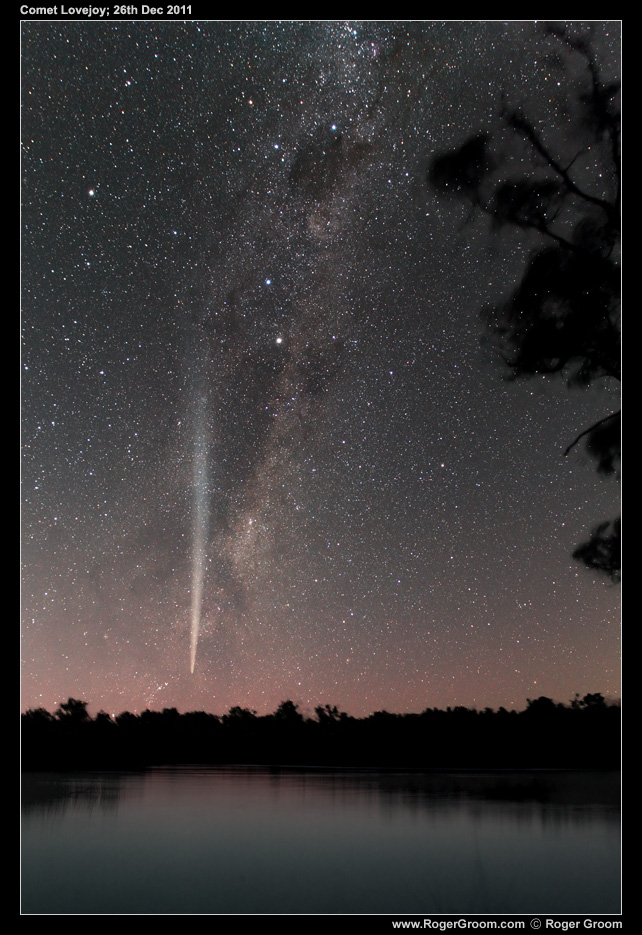

Figure 44.2 below - Comet C/2011 W3 (Lovejoy)

Image Credit: Roger Groom in Western Australia

45: 2007 – Vandi Verma

Author: Ian Kemp

Vandi Verma was born in Halwara in India. Her father’s air force career meant regular moves and, as a 21st century woman, she was able to target and pursue a career that would have been unthinkable to many ambitious female scientists, up until only a few decades ago. After a degree from the Punjab Engineering College, she was able to become a student in the USA, and completed a Masters and PhD at Carnegie Mellon in 2005. No problem either with her chosen field of study: robotics which also, just a few decades previously, very few people would have thought at all relevant to astronomy.

While doing advanced study, she obtained a pilot’s license and fought her way through the complex bureaucratic jungle to get security clearance to work for NASA. In 2007, she joined the Jet Propulsion Lab and moved into the Mars team. This is how she became qualified and put herself in the right place to become one of the ‘drivers’ of the NASA Mars Rovers. Vandi’s story illustrates that in the modern world of astronomy, opportunities depend on ambition and hard work, and also in recognising the amazingly wide range of skills needed to pull off today’s mega-projects, which rely on large teams of people.

Vandi has worked on all three of the Mars Rovers - ‘driving’ in this case means analysing 3D images of the target area, meetings to discuss objectives with the science team, detailed analysis of possible obstructions and hazards, and programming in advance the movements and activities of the rover; followed by careful monitoring in case anything might go wrong or interrupt the progress of the multi-billion-dollar mission. The personal dedication includes changing lifestyle to match the Mars day, which is 40 minutes longer than an Earth day.

This is today’s astronomy - astronauts may or may not go to Mars but, for today, the rovers and their large teams of engineers and computer specialists are delivering results in planetary science.

Figure 45.1 below - Vandi Verma: Vandi is at work "on" Mars, using 3D specs to analyse the terrain.

Image Credit: NASA

Figure 45.2 below - Mars: High-resolution image of Mars from Curiosity rover

Image Credit: NASA

Video: Practice runs on Earth followed by the real thing on Mars (Science Channel).

46: 2020 – Afterword

Author: Lesa Moore and Ian Kemp

Some lessons we may take from this series on "Astronomy through the Ages" ...

Theory and experiment are both important. Some of the most important breakthroughs in astronomy have come just from people using their heads to do ‘thought experiments’ - a great tradition from the Ancient Greeks right up to Albert Einstein. But equally important breakthroughs have come from experiments or observations that reveal new phenomena or make more accurate measurements that disagree with previous experiments, observations or theories: Galileo, Brahe/Kepler, Rubin, Davis and Schmidt fall into this category.

Until very recently it was very difficult for women to successfully pursue a career in astronomy on an equal footing with men. It would be heartening to think that this is different today, but it may be the case that time is still needed to overcome the legacy of institutional sexism.

In the past, individual names jump out of the pages as the great contributors but, today, it’s increasingly the case that astronomical advances come from large multi-disciplinary teams working together, and it can be hard to pinpoint individuals who are responsible for modern breakthroughs.

Finally, despite the importance of multi-million-dollar big science projects (spacecraft, LIGO, planetary rovers, SKA for example) there is still a place for the individual contributors, and we’ve met a few amateur astronomers who’ve played an important role in modern astronomy simply by virtue of their determination to make a contribution.

Figure 46.1 below - The Flammarian Woodcut

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons

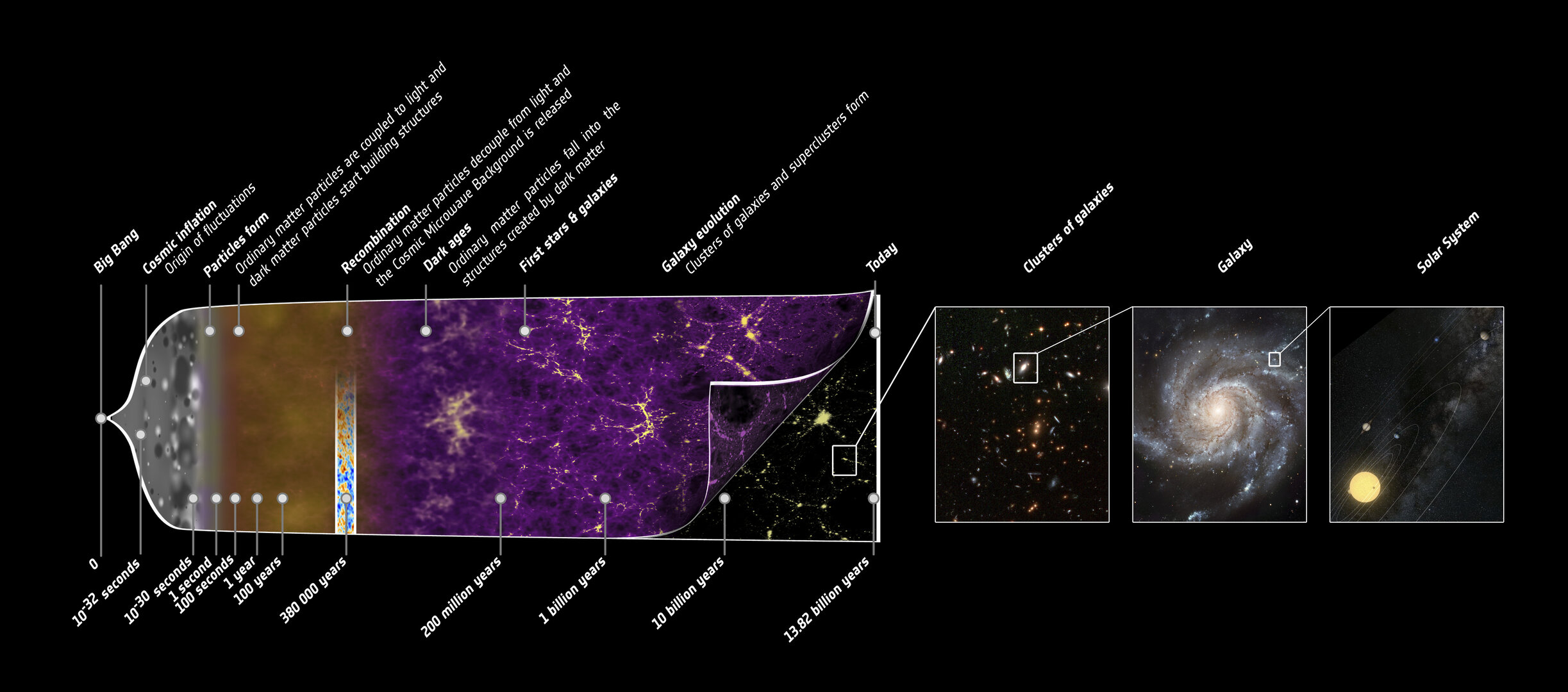

Figure 46.2 below - History of the Universe

Image Credit: ESA

Figure 46.3 below - Galileo demonstrates a telescope

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Figure 46.4 below - Square Kilometre Arrray (conceptual)

Image Credit: CSIRO